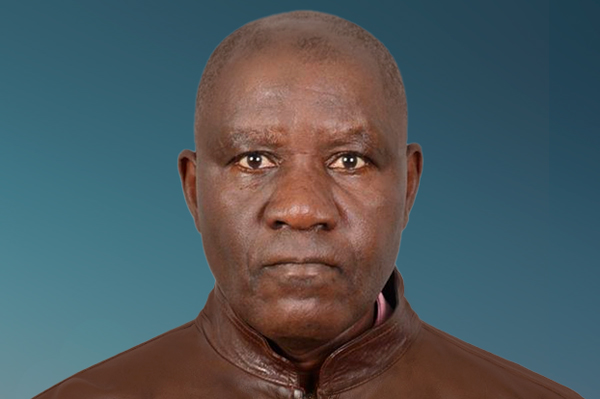

Hi, my name is Nfortentem Aaron and I am from Bamenda, in the Northwest Region of Cameroon. I have been living with diabetes, hypertension and cerebrovascular accident for about five years.

I'm sharing my story because I believe it will go a long way to raise awareness on the negative impacts and burden of living with NCDs on the population, especially individuals like me who can barely afford out-of-pocket expenses for health services. Through my NCD Diary, I call on decision-makers to action necessary changes and adopt measures to support all people living with NCDs.

16 November 2023

Living with NCDs in an armed conflict

In 2016, an armed conflict broke out in my country. At the time, farming was the main source of income for myself and my family. The conflict caused challenges in my job and livelihood; the market road became inaccessible for vehicles, so I used to have to carry the farm produce to the market myself.

In 2017, I started experiencing fatigue and excessive thirst, which I assumed was due to the hard work I was doing. However, I soon started developing wounds on my legs that took longer than normal to heal, and my vision became blurry. My neighbours would regularly help to clean my wounds because going to the hospital was very risky due to the armed conflict. A friend of mine, who had experienced similar symptoms, insisted that I visit the hospital as he suspected that I had diabetes, but I hesitated to do as he advised.

Later on, I started developing backaches and heart palpitations. Noticing how frequent they were, I decided to visit the doctor at the Bafut Community Health Center, who diagnosed me with diabetes and prescribed a long list of generic medications including amlodipine, metformin, lisinopril, hydrochlorothiazide and pyridoxine. As this was a primary care clinic that does not focus on NCDs, I paid in full for health services as there were no subsidies for the treatment cost, and I had no form of health insurance because I had no stable source of income. I did not understand the implications of diabetes and could not manage the condition properly with treatment due to its high cost. A few months later, I had a stroke which left the right side of my body paralysed. The doctor said it was caused by high blood pressure and the heart palpitations I experienced were a sign of this. This caused me to switch to painting as an alternate source of income as it was less stressful compared to farming.

Due to the conflict, I lost most of my belongings and had to move to somewhere safer. I did odd jobs in order to pay for hospital expenses, which most of the time did not cover the cost of a consultation. Not being able to pay out-of-pocket for treatment at times meant not having access to any form of health service.

31 January 2024

Inequities amongst disadvantaged groups

When I moved to Mulang in the Northwest region of Cameroon in 2019, which by then was affected by the conflict, I met Pa Lucas, a retired security guard living with diabetes and hypertension. He did not receive financial support from anyone and like me, didn't have health insurance or a pension plan because he couldn't afford it. As a security guard on low pay, he was also not included in the national retirement scheme. His condition kept deteriorating as he could not afford out-of-pocket payments for health services. He was already advanced in age and was not physically fit for any job because of his health issues. He resorted to begging and survived on donations made by some people in the community. Pa Lucas often visited the Regional Hospital for lab tests and to get medication. Each time he visited without enough money, the health workers would either leave him unattended or attend to him last, prioritizing those who could afford the full payment. When they did attend to him, he only received the services he could afford, with no subsidies, no matter how bad his condition was. He would often go without money and then get thrown out of the hospital after receiving insults.

Pa Lucas’ story is not unique: the inequities he has faced due to a lack of financial resources and the poor treatment by the health system are common challenges for those of us who try to access government hospitals or clinics for vital health services.

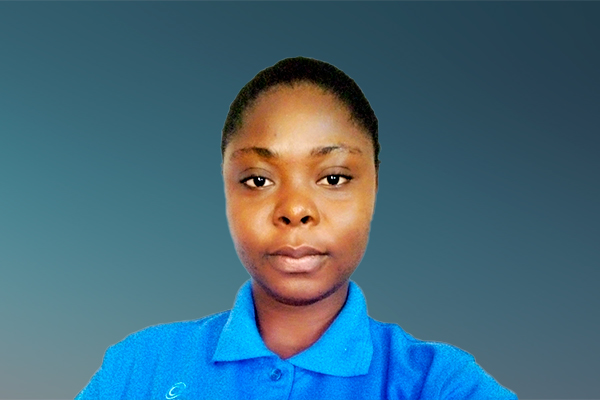

Mrs. Manka’a for instance has a similar story. She is a widow who lives in a remote area in Mulang with her three children and suffers from diabetes which resulted in her losing her sight. There are no clinics in her area. She only receives income from farming, which is hardly enough to feed her family. In addition to the geographical barriers to access, Mrs. Manka’a does not receive any financial assistance which means she cannot afford healthcare.

At the Nkwen Baptist Hospital, I met other people living with NCDs, including cancer. The most common challenge people shared was accessing financial support. The armed conflict in Cameroon has made our communities unsafe, leaving most of us internally displaced with no money or property. We have to start over in new environments, find shelter and jobs to source income with very limited job opportunities. We are only able to find jobs like working on people's farmlands, cleaning and brick laying with no good pay to take care of our daily expenses. This has contributed greatly to our inability to access health care.

21 February 2024

Closing the gap

Living with NCDs and not being able to afford or access health services is a difficult burden for us to bear.

Many people living with NCDs in Cameroon lack access to health services and as a result are not diagnosed. When they do access health services and receive a diagnosis, there is no proper follow-up to support the treatment and management of their condition. Many others do not even have an idea of what NCDs are, nor of their signs and symptoms or how to prevent NCDs.

It is about time the government, the Ministry of Public Health, and civil society organisations join forces to effectively implement measures to reduce the burden of NCDs at a national level. The Ministry of Public Health should make sure that people like me living with NCDs have access to health services at all levels. NCD clinics or units should also be created in rural areas to increase access to health care for those unable to reach urban areas, as seen with Mrs. Manka’a. I also urge civil society and the Ministry of Public Health to put additional efforts into raising awareness of NCDs, with a focus on reaching remote areas. These populations are at greater risk of having undiagnosed or untreated NCDs and are therefore more likely to have greater morbidity and mortality. In addition, NCDs should be included in the national budget, and the cost of NCD health services should be subsidised like they are for services for infectious diseases, so that we can receive access to diagnosis and treatment despite our financial circumstances and the ongoing conflict.

Lastly, people like us living with NCDs should receive proper follow-up. This could be done through community-based care by assigning health workers to patients to improve access to care when needed. This could also reduce instances of discrimination by health workers, as patient needs are better understood. Assigning health workers to patients can also address geographical barriers to access, which will enable follow-up for people living with NCDs regardless of their location. Health workers can visit people in rural or more remote areas in the comfort of their homes and put in place arrangements for follow-up to support people in managing their conditions.

NCD Diaries

Inequalities around access to health services should be addressed to reduce the burden for all groups of people living with NCDs.

Nfortentem Aaron, lived experience of multiple chronic conditions, Cameroon

About NCD DIARIES

The NCD Diaries use rich and immersive multimedia approaches to share lived experiences to drive change, using a public narrative framework.