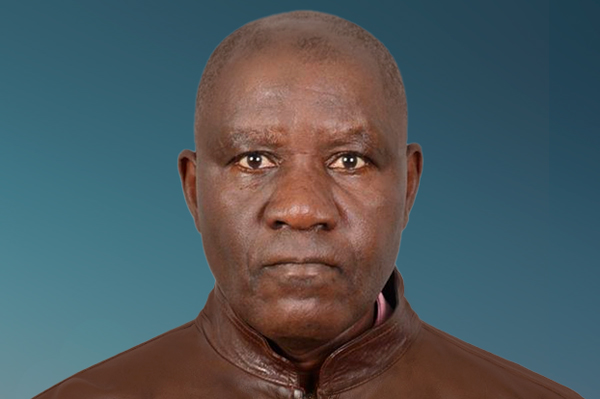

My name is Jean Marie Blaise Migabo.

I'm sharing my story because I belong to a family of people with asthma. Close to me, my father and one of my brothers suffer from it.

1 November 2021

Far away to save...

I was 12 years old, and it was supposed to be a morning like any other. But on this April day, it was a different story after I was awakened early by my father's sneezing and coughing.

Living with asthma for years, we were used to him going into crisis at home but within a few minutes he would recover. But that day, he coughed and sneezed so much that we started to worry.

The problem this time? The weather on that April morning, a rainy day and therefore an abrupt change for him, especially as his usual Ventolin spray had run out. He only had a few Aminophylline tablets to fall back on, which he had been careful to keep with him. Fortunately, it worked, but after a time of severe crisis. And the worst case, in our locality, there was only one pharmacy about 12 km away, the nearest place.

Although as a primary school teacher he does not have much money, but being a state functionary, he is entitled to a civil service mutual insurance. Here I have to mention that there is no national insurance scheme for NCDs that is open to the whole population.

However, the process for my father to receive his medication is lengthy and complicated. First, he must go to a specialist to get a prescription. It takes him three days, as the country has less than ten pneumologists for 12 million inhabitants. He then must travel to the national office, Mutuelle de la Fonction Publique, to get a form allowing him to access his medicine at the price of the insurance company.

The national office is located in Burundi’s capital, Bujumbura. This is more than 80 km from his residence. This journey is physically difficult due to his condition and the fact that he must pass through rough roads. This, in addition to the administrative heaviness of the process, incurs a lot of expenses that he had to pay out-of-pocket.

As a medical doctor and care partner to my father and other relatives living with NCDs, I have supported them in navigating this process to receive care, and also have contributed financially for my father’s medicines when needed. Through my experiences I have discovered that this costly process is the same for other chronic conditions, creating challenges for many people in Burundi. I will come back to this in my 2nd entry...

2 November 2021

When the cost sets a blow

Through my experiences as a doctor and care partner, I’ve witnessed many challenges faced by people living with NCDs in Burundi.

I remember a young man in his early twenties, diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. He couldn't easily get his insulin because he couldn't afford it. There are some government-led as well as private (NGO) centres in Burundi that have been set up to give insulin to people under age 25; however, these were located very far from his home and would require a travel cost that he, still at school, could hardly afford.

Those lucky enough to get insulin had to deal with the lack of refrigerators for storage. They would be forced to store it at the nearest centre, or in a way that was not safe. The lack of facilities for medicine storage decreases the supply and therefore increases their cost.

I also remember this woman who had been living with high blood pressure for years. Monitoring was not too complicated as she lived close to a basic health care facility, and her insurance covered basic tests. However, things became difficult after she had a hypertensive crisis. A doctor from a local facility suggested that she undergo an electrocardiogram, a heart ultrasound and a fundus (the eye exam to diagnose diabetic retinopathy) at a facility outside of her province, as those exams could not be performed there. These were expensive tests that were not covered by insurance, which she struggled to afford as a widow with no paid job.

Cancer? Sometimes I'm afraid to talk about it when I think of this young girl, age 19, with breast cancer. To confirm her pathology, she had to send her sample abroad because there was no pathology lab in Burundi. Had it not been for the help of charitable people, this would not have been possible, as she was very poor and this service is expensive. Due to these factors, the diagnosis was made at an advanced stage. She had not even had access to a mammography screening, as these machines are scarce in Burundi, which increases their cost.

These stories reflect the challenges that come with limited health services and not having access to health insurance that covers specialised health care beyond basic care in primary facilities. Action on affordability and Universal Health Coverage of NCDs is more than necessary in Burundi. I will come back to this in my final entry...

13 January 2022

Small steps making a great move…

The number of people living with NCDs increases day after day, but unfortunately, the availability of services and staff for their care does not follow the pattern.

In Burundi, there are very few NCD specialists, and therefore people living with NCDs often struggle to find care or even a diagnosis for their condition. There is also a lack of diagnostic tools, which is reinforced by the fact that the few specialists that exist are concentrated in the city of Bujumbura alone, to the disservice of those living in the provinces.

Limitations in NCD services have driven up the cost of care in Burundi, including diagnostic services and medications, which are very expensive compared to the average Burundian’s income. This is exacerbated by the fact that there is no accessible health insurance scheme in Burundi, with less than 20% of Burundians having access to health insurance, of which less than 2% are in the private and informal sectors. Public servants are subject to a compulsory mutual insurance scheme with contributions paid for through their employment. For the many people in the private and informal sectors that do not have health insurance, this is likely because of a lack of awareness as well as cost, with many private companies not willing to spend money on health insurance for their staff.

In view of the above, I call upon the Burundi government to increase investment in health services, especially those related to NCDs. Incentives and training programs should be launched to increase the number of NCD specialists in Burundi and expand access to care services for people living with rural areas. Efforts must also be focused on expanding and establishing additional medical facilities that are equipped to diagnose a wide range of NCDs.

Moreover, I call upon the Burundi government to accelerate efforts to implement Universal Health Coverage. A public mutual society fund could also be established to encourage the formation of a collective society through pledges or a policy of small but compulsory contributions, under the supervision of the government. For these actions to be successful, people living with NCDs must contribute to every step of the decision‑making process.

Finally, people living with NCDs must play their role, especially in advancing action towards NCD prevention and raising awareness of NCDs alongside decision-makers. The involvement of people living with NCDs is critical to account for the general scarcity of information about NCDs ‑ despite their prevalence ‑ in Burundi.

NCD Diaries

Chronic diseases affect not only the person with the disease, but also their surrounding community, starting with the family. I share my story in the hopes of advancing the NCDs and UHC agenda, to improve wellbeing for all.

Jean Marie Blaise Migabo, lived experience of chronic respiratory disease, Burundi

About NCD DIARIES

The NCD Diaries use rich and immersive multimedia approaches to share lived experiences to drive change, using a public narrative framework.