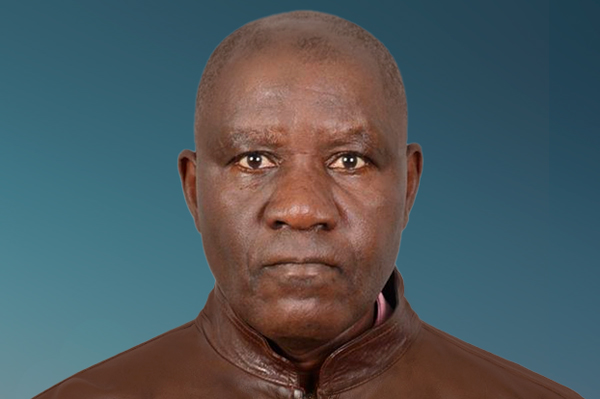

My name is Samuel Kumwanje and I am from Malawi.

I'm sharing my story because it is crucial that affordable services are accessible for people living with kidney disorder and other NCDs in my country. Work still must be done to make sure that conditions are diagnosed early and treated with the right care for the entire population, regardless of socioeconomic background.

17 September 2021

My journey with kidney disorder

My name is Samuel Kumwanje from Malawi, and I was diagnosed with kidney disorder in 2004. Born in 1976, I spent my youth in a rural area where there is a lack of information about kidney disorder. From age 12, I began suffering significantly from symptoms including body pain, loss of appetite and vomiting, yet no one could understand the cause. A district hospital referred me for a checkup at a public hospital (at which services are provided free of charge), and my results were sent to the UK for further investigation. However, no diagnosis was made because tests related to kidney performance were not conducted – an indication towards lack of focus on kidney disorder in our health system.

My early symptoms soon became complicated, such that my whole body was weak and I could not walk or support myself. Without a diagnosis, I turned to herbals from the local communities that my father sourced. I remember one being so bitter that my body would tremble soon after taking it. I believe that these herbs may have worsened rather than solved my kidney condition.

In June 2004, my symptoms increasingly worsened. I visited many hospitals, but doctors still did not diagnose the problem. Every time I visited the hospital, the doctors would interpret my symptoms as malaria and prescribe malaria treatment.

Finally at NGO-run Likuni Mission Hospital, they diagnosed me with kidney failure because one of my sisters-in-law, who is a nurse, advised me to request a check of my kidney performance. This was a private service covered by my Medical Aid Society of Malawi medical insurance, made available through my employer. At this time, I had no information about kidney disorder, yet it was a happy moment because I would finally receive treatment.

By the time I was referred for dialysis, Malawi had only one dialysis unit located in Lilongwe. I was based almost 330km away in Balaka, which was a long way to travel twice weekly for treatment. This is the time I learned that affordability of dialysis services is limited for Malawians. Kidney disorder requires frequent laboratory tests, most of which are offered free of charge in public hospitals. However, some essential lab tests must be done in expensive private ;laboratories. As I have access to medical insurance, I receive coverage for these tests, yet there are others who do not. I will touch upon this and related challenges in my next entry.

19 November 2021

My Community: Our life on dialysis

I started my dialysis in 2004 at Kamuzu Central Hospital, a government-run hospital in Lilongwe, alongside my friend Godfrey, who had been on dialysis at this point for 3 years. With four machines available at this public hospital in Malawi, access to dialysis services for both of us was hassle-free and without charge.

However, by 2007, challenges started to emerge with the machinery as the number of people with kidney failure receiving dialysis increased to 7. As overuse of the limited machinery worsened, we formed the Kidney Foundation – Malawi, an association to amplify the needs of people in the dialysis unit. Among several objectives guiding the association, advocating with the Malawi Ministry of Health to prioritize renal conditions was one.

In 2012, the Kidney Foundation called for the transfer of all people receiving dialysis from the Kamuzu Central Hospital to a newly opened dialysis unit at Dyoung Luke Hospital, which was equipped with much higher-quality machines. As it was a private hospital, the Malawi government agreed to cover dialysis costs for myself and the others living with kidney failure for one year. However, as the unit was in a rural area, travel was difficult as many of us live below the poverty line and without cars.

In 2013, the Malawi government was able to increase the number of dialysis machines to 10 at the public hospital, and we were all transferred back to receive the service free of cost. However, within a year, the number of people accessing the service increased to 64, posing significant challenges such as long wait times. Some patients lost their lives due to fluid overload. At present, only two public hospitals in Malawi offer free dialysis services, with few machines for many patients. The only private hospital with more machines is unaffordable for many local Malawians.

By the time I joined the Mw-NCDA, I had become close to a diverse number of people living with NCDs. As the project coordinator for the NCD Alliance’s Our Views, Our Voices initiative, I have observed that there are many common challenges for people living with NCDs, including lack of affordability of medications and treatment. The majority of us also received late diagnoses which contributed to and worsened our conditions. From these experiences, I have come to understand the importance of access to Universal Health Coverage (UHC) for people living with NCDs in Malawi.

23 December 2021

This is the right time for change in the NCD response

Malawi is one of the developing countries that is still behind in terms of our advancing NCD response, including diagnosis, treatment, care, support and meaningful involvement of people living with NCDs in the decisions that affect our lives. This can largely be attributed to lack of political will from stakeholders involved in the NCD response.

Through my lived experience and involvement in the Our Views Our Voices initiative, I have learned about the gaps in service delivery and affordability of care when it comes to NCDs, and the lack of understanding and stigma around NCDs in Malawi. I have observed the limited involvement of people living with NCDs in decision-making and political processes, which is critical to address. I have also observed the lack of public awareness campaigns for NCDs, which is important as it is us, the people with lived experience, who can build trust with the community and spread the message that you can live with NCDs as long as you are able to adhere to treatment.

The importance of prevention measures is not taken into consideration enough, as these measures generally incur lower costs than that of treatment, care and support for people living with NCDs. As people living with NCDs, we observe that alcohol and tobacco are two of the most common risk factors of NCDs. Therefore, I call on the government to restrict the use of alcohol and tobacco by limiting their sale in open places, where even children can have access. I also call for the banning of advertisements that mislead the public to believe that some of these commodities are harmless to people.

Most importantly, people living with NCDs must be able to easily access NCD services, which is not currently the case for everyone in Malawi. As I have shared in my diary, there are challenges when it comes to diagnosis as well as affordability of treatment services. Not all NCD services are provided for free in public hospitals, whilst those that are free often have limited capacity, and medical insurance packages do not provide full coverage (for those lucky enough to have access to insurance at all). I therefore call on the government and donor partners to make sure that these challenges are promptly addressed, and to prioritize the rollout of UHC, inclusive of all NCDs, in Malawi.

NCD Diaries

It’s not easy to live with kidney disorder when you are the bread winner of the family, and it's challenging when you are employed because you need to satisfy your boss whilst at the same time adhering to dialysis sessions. My goal is to shed light on the challenges that myself and people living with NCDs in Malawi face when it comes to affording care, in the hope for positive change around Universal Health Coverage.

Samuel Kumwanje, lived experience of liver, gastroenterological, genitourinary, renal disorder, Malawi

About NCD DIARIES

The NCD Diaries use rich and immersive multimedia approaches to share lived experiences to drive change, using a public narrative framework.